The 9 Stages of the Hero’s Journey and How to Use Them

What is the true purpose of storytelling?

You might say it’s to uplift us, or to comfort us in times of trouble. Others will argue storytelling serves to teach us morality, the meaning of good versus evil, or the value of inner strength. Yet, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey goes deeper than all of those things.

The Hero’s Journey is about exploring human nature and charting our common path from childhood to adulthood, regardless of who we are or what we struggle with. Not only that, but it embodies universal themes of growth and change, making it the perfect foundation to build your own unique story from!

What Is the Hero’s Journey?

Contents

Most writers who have studied story structure have come across the concept of the Hero’s Journey at least once or twice.

Most writers who have studied story structure have come across the concept of the Hero’s Journey at least once or twice.

Popularized by Joseph Campbell, the Hero’s Journey was part of his idea of the “Monomyth,” a term describing the universal progression of all human storytelling. He developed this while studying mythology from cultures across the world and throughout history, writing about them in The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

As a follow up, Christopher Vogler wrote The Writer’s Journey, further distilling the ideas of Campbell into a usable storytelling guide.

The result is one of the best storytelling tools around.

At its core, the Hero’s Journey is a form of story structure just like the Three Act Structure. However, in comparison the Hero’s Journey is much more broad, and is something you can see at play in almost every story—regardless of how anti-traditional it may be.

This is because the Monomyth builds on ever-present patterns of growth and change, something humans have been obsessed with forever.

- What is my purpose in life?

- What does it mean to grow up?

- Is there something greater out there?

- What will happen when I die?

These questions have always echoed in the human mind, and been reflected in our storytelling as a result. Thus, the Hero’s Journey is so powerful and omnipresent because it resonates with a core part of our human experience.

“A blunder—apparently the merest chance—reveals an unsuspected world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood… They are the result of suppressed desires and conflicts. They are ripples on the surface of life, produced by unsuspected springs. And these may be very deep—as deep as the soul itself.”

– Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

Using the Hero’s Journey in Your Own Novel

Of course, this is all well and good, but how can you use this Monomyth in your own writing?

Well, one of the best qualities of this structure is that it ties together both your characters and plot. Rather than just being a story structure, the Hero’s Journey can also act as something of a character arc. That’s the most helpful thing about these principles—they apply not only to your plot, but your protagonist’s arc as well, helping you build a more cohesive story.

When combined, you have a powerful recipe for engaging your readers!

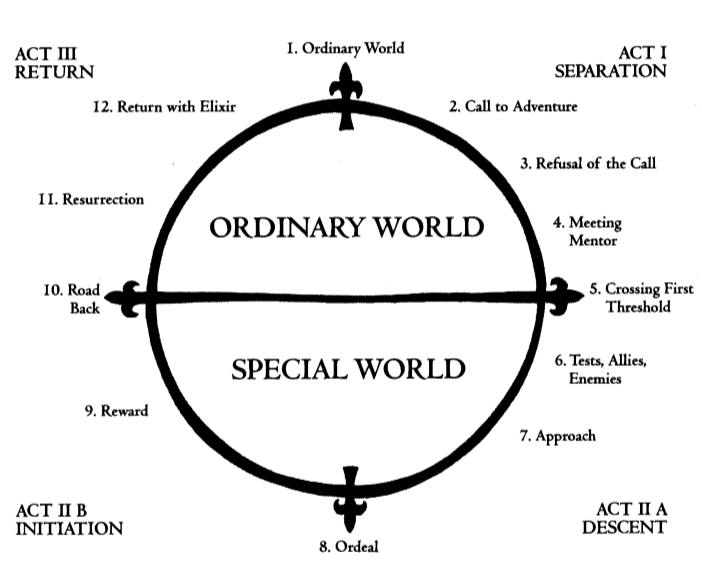

Overall, the Hero’s Journey is split into two halves: The Ordinary World, and the Unknown World. The Ordinary World is exactly what it sounds like—your protagonist’s everyday life, complete with all of their flaws and insecurities.

However, a problem is brewing beneath the surface, and this is what will force them to leave home and enter the Unknown World. This Unknown World is where they’ll be tested and forced to grow as a person. Along the way they’ll gain new allies and skills, until they finally return to their Ordinary World to heal it’s suffering and take their place among the heroes.

Throughout this structure, your protagonist’s inner development will mirror the conflict of the story, giving your novel a cohesive and resonant feel. With that said, let’s look at the nine stages of the Hero’s Journey and how to incorporate them in your own storytelling!

The 9 Stages of Campbell’s Monomyth

The Ordinary World:

The start of the Hero’s Journey finds us in the Ordinary World, where readers are introduced to your setting, meet the starting cast, and get to know your protagonist. Essentially, the Ordinary World provides a baseline that will make the Unknown World your protagonist later encounters stand out.

Because of this, you don’t want to neglect this important setup.

Without seeing where your hero is starting from, a world full of magical purple unicorn dragons could be entirely normal to them. Instead, you need to you start your story by showing their normal everyday life in suburban Wisconsin. It’s the contrast between these two worlds that makes them feel impactful.

Alongside this, the Ordinary World also sets up the inner struggle your protagonist will need to overcome during their character arc. It shows how they’ve been living before their journey begins and foreshadows the cracks under the surface. Without this critical knowledge of the Ordinary World, the reader has no metric by which to measure your character’s growth or the growth of their world.

The Call to Adventure and Refusing the Call:

If you’re already a fan of the Three Act Structure, then the Call to Adventure will likely feel at least somewhat familiar.

This is because the Call to the Adventure mimics the Inciting Event and Key Event from the Three Act Structure. Here, your protagonist will learn of the coming conflict and get their first taste of the journey to come—though sometimes they are whisked away with little choice. Most often they’ll also refuse this call, helping your reader better understand the stakes of your story.

If your protagonist has reason to be afraid, then your audience does as well.

This stage allows you to build suspense, foreshadow the power of your antagonist and the dangers ahead, and show off your protagonist’s flaws in action. Are they too timid, headstrong, selfish, or careless? Incorporate this into their Refusal of the Call and show how it will hinder them on the journey ahead.

Overcoming Resistance and Meeting the Mentor:

Now that a Call has been issued, your protagonist will be feeling afraid, hesitant, or even outright resistant to beginning their journey.

Overcoming this resistance requires a period of counsel, where they’ll get advice and encouragement from mentors and allies. Here you’ll prepare your protagonist and audience for what’s coming, while also fitting in some last minute worldbuilding and plot development before your story picks up steam.

Your protagonist will begin collecting the tools and wisdom needed for the road ahead, though they won’t be completely prepared for a while yet. Their inner struggles will continue pushing against them here, and they may neglect important information they’ll regret later on. Still, they’ll also show promise, usually in the form of some redeeming quality that lets your readers know there is hope for them to grow.

Crossing the First Threshold:

This is the true beginning of your story.

Here your protagonist will Cross the First Threshold into the new, Unknown World, officially committing themselves to the journey ahead. There is no turning back from this point, and no returning to the Ordinary World until they’ve completed their quest and grown past their flaws.

Your protagonist will have to prove themselves to make it this far of course, even though they haven’t overcome their inner struggle just yet.

Just as they showed a redeeming quality while Overcoming Resistance and Meeting the Mentor, they’ll need to prove this redeeming quality again to cross into the Unknown World. As an example, Bilbo Baggins temporarily overcomes his fearfulness and leaves the Shire, while Mulan overcomes her self-doubt and joins the Chinese army. However, some characters will be forced into this Unknown World, like when Simba is driven from the Pride Lands by Scar.

Tests and Trials:

Your story has officially entered the Unknown World, and this is when a period of Tests and Trials begin for your protagonist.

Here they’ll gain new allies, new enemies, and new skills. They’ll be beaten down repeatedly, only to get back up again that much stronger and wiser. Essentially, this period is all about preparing them for the bigger battles that lie ahead.

This means that the Tests and Trials period is important for a variety of reasons.

It provides a stark contrast from the more stable Ordinary World and thrusts your protagonist into their new life. However, it also gives them the opportunity—through their new experiences—to prove their strengths, befriend others in your cast, and begin to threaten your antagonist. Overall, these tests will form nearly a quarter of your story’s overall runtime as you approach the Major Ordeal.

The Major Ordeal:

Perhaps confusingly named, the Major Ordeal is not the Climax.

Instead it corresponds with the Midpoint of the Three Act Structure, and shifts your protagonist from a period of reaction to action. After this point, they’ll finally be able to actively drive your plot forward, rather than just being pushed along against their will. They’ll also be rewarded for their success, either through a new tool, new allies, or new knowledge.

The Major Ordeal itself will feature a moment of growth that cements your protagonist’s progress. They’ll have to face their biggest conflict yet, giving them a chance to show how far they’ve come from their Ordinary World. However, don’t let them get ahead of themselves.

They haven’t overcome their inner struggle yet, though they may think they have.

To pick on Mulan again, her Major Ordeal occurs when she retrieves the arrow from the top of the pole in the middle of camp, proving her cleverness and intelligence. She has gained the acceptance of her comrades, but she is still living in disguise. This will come back to punish her later, just as your protagonist’s flaw will come back to punish them.

The Road Back:

With the Major Ordeal behind them, the Road Back prepares your protagonist to face the finale of your story.

They’re now driving the plot, seeking out your antagonist or otherwise planning their defeat, and likely beginning the trek to wherever their final showdown will take place. Here your pacing will speed up as well. You’re preparing for a climactic showdown, and both your cast and your readers are ready to see this journey come to its conclusion.

This creates the perfect opportunity to remind your protagonist of the stakes.

In the afterglow of the Major Ordeal, you need to show them why their journey isn’t over yet. Reveal the cracks still left by their flaw, and remind them that no matter how much they try to cover them up, they must deal with them soon. The conflict is far from over, and there’s still danger ahead.

Mastering the Journey:

With your story coming to its close, its time for your protagonist to prove they’ve mastered their journey—and as you can probably guess, this overlaps with the Climax and the Climactic moment from the Three Act Structure. Here they’ll do battle against your antagonist and face their final test, hopefully overcoming their inner struggle in the process.

As a result, everything in your story needs to come together here.

All of your themes, subplots, characters, symbols, motifs—it’s called the Climax for a reason! Of course, this is also the culmination of your protagonist’s arc. Here they’ll face the most difficult test of their flaws, and will have to use all of the knowledge, skills, and alliances they’ve gained to survive.

Ultimately, without the journey they just went on, they would never be able to succeed.

Returning with the Elixir:

With your story’s conflict resolved, it’s now time for your protagonist to recover. To Return with the Elixir references the end of many myths where the hero brings the rewards of their journey back to their home village, healing the lives of everyone around them—not just their own. In terms of the traditional Three Act Structure, this mirrors your Resolution.

Essentially, your goal in these final scenes is to complete the circle of your story.

At the end of many adventures the protagonist returns home to their Ordinary World, experiencing echoes from the start of their journey. Yet everything feels different, and they quickly realize how their quest has changed them. Others don’t make a physical return, but instead see similar situations to those they struggled with or felt uncomfortable in at the start, this time unfazed by what seemed so intimidating before.

Either way, these final moments will be bittersweet, joyful, and maybe even a bit sad.

Most importantly, they’ll provide an important sense of catharsis for your readers, a release of the emotional tension your story created. So—to use this ending to its full effect—make sure you give your readers a moment to relax with your cast before they close the back cover.

Understanding the Monomyth

At the end of the day, the Hero’s Journey embodies patterns seen in almost all human storytelling, and it’s also a great tool for writers wanting to more deeply understand their own stories. While it’s not without it’s flaws, it can still serve as a great starting point for telling your own epic adventures!

Of course, the Hero’s Journey isn’t the only form of story structure out there. If you’re interested in exploring everything else story structure has to offer, I hope you’ll take a moment to check out The Complete Story Structure Series, a collection of articles on The Novel Smithy dedicated to everything structure.

Hi, I have four books out and a new one almost ready. This may be the best explanation of the Journey I’ve read. And, I’ve read a lot, including Hero with a Thousand Faces and the Writer’s Journey. I especially like your take on Crossing the Threshold and the Major Ordeal. Those two entries helped clear a lot of fog on the subject for me.

Thanks.

Charles Hampton

Glad to hear it Charles! 🙂