How to Write a Hero: The 12 Stages of the Hero’s Character Arc

Heroes are integral to the history of storytelling.

Not only are heroes beloved, but they’re practically required for many stories. Classic heroes such as Robin Hood and King Arthur mix with modern variations like Simba and Shane to form a formidable pantheon. However, perhaps more interesting than who we consider a hero is what all heroes have in common: the hero’s character arc.

This hero’s character arc demands that the hero leave home, sent away to prove themselves and grow into the leader their community needs. Their journeys are always ones of service and self-sacrifice. Most importantly, this hero’s character arc is something you can use to write memorable, compelling heroes all your own!

How to Write a Classic Hero: The Hero’s Journey

Contents

Whenever someone asks me how to write a hero, I immediately point them towards Joseph Campbell.

Whenever someone asks me how to write a hero, I immediately point them towards Joseph Campbell.

After all, we can’t talk about heroes without first talking about the Hero’s Journey.

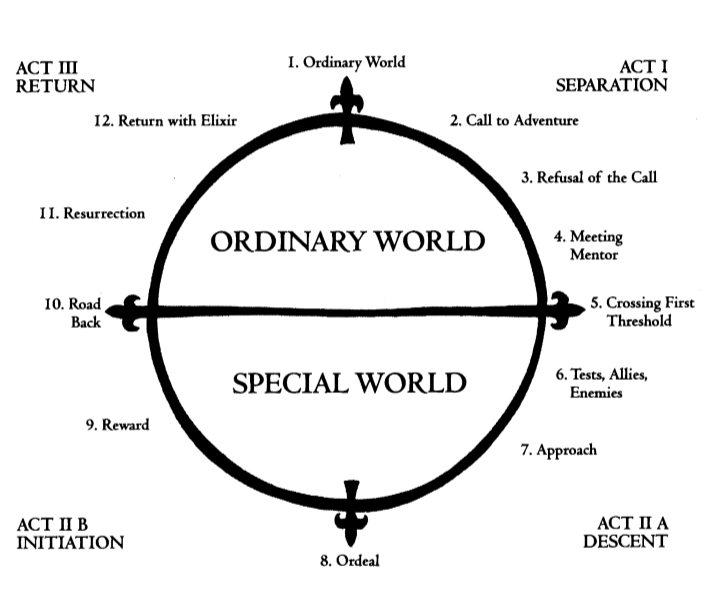

At its most basic, the Hero’s Journey is a common pattern all hero characters follow, popularized by Campbell.

It follows a character as they’re called on an adventure, face a series of trials, and undergo a final challenge where they prove they’ve grown into the hero’s archetype. However, unlike similar story structures like the Three Act Structure, the Hero’s Journey doesn’t stop there.

You see, the success of society is just as important as the success of the hero themself.

This is why the Hero’s Journey requires the hero to return home and share their new skills and knowledge, helping their society heal and prosper as the final phase of their journey. Without that crucial step, their hero’s character arc is incomplete.

“Heroes are symbols of the soul in transformation, and of the journey each person takes through life. The stages of that progression, the natural stages of life and growth, make up the Hero’s Journey.” — Christopher Vogler

While Campbell’s legacy may be complex these days (especially because of his rather toxic views of women), the basic structure he outlined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces remains one of the best explanations of the journey characters must go on to be considered a hero.

You can find his Hero’s Journey at work in nearly every myth, novel, movie, and play out there—and, despite Campbell’s views, there’s absolutely no requirement for the hero character to be male or female.

Understanding the Hero’s Inner Journey

Despite how useful Campbell’s work is on its own, there have been some important additions that have not only clarified his ideas, but added new and unique interpretations. Most notably is The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler, which turned the Hero’s Journey into a more usable guide for writers.

In particular, Vogler helped create the idea of the hero’s character arc by separating the Hero’s Journey into two halves:

The Outer Journey (story structure) and the Inner Journey (character development).

This Outer Journey is all about the plot of the Hero’s Journey, which we discussed above, while the Inner Journey focuses on the growth and psychological state of the hero. This Inner Journey is the foundation of the hero’s character arc, and you can see it at work in any of the three different primary character arcs. It’s this journey that takes a standard character arc and turns it into a hero’s arc, even if the hero fails at the end.

This understanding of the hero’s Inner Journey is incredibly valuable, because almost all writers will wonder how to write a hero at some point. Heroes are an integral part of our storytelling language, and this pattern of the hero’s character arc provides a guide to help you create the type of memorable, compelling heroes readers can’t get enough of.

The 12 Stages of the Hero’s Character Arc

Starting in the Ordinary World:

In every hero’s character arc, the hero begins in their ordinary world. This is their home and community, and it gives the reader a baseline from which to judge their later growth.

At this stage the hero is often ignorant of the outside world, but still feels a certain level of discontent. Something about their ordinary world isn’t right, and this something will slowly push them to venture into the unknown in hopes of solving this problem.

#1: The Call to Adventure:

The Call to Adventure is a pretty well know plot point within the hero’s Outer Journey. Here they’re introduced to the conflict and pushed to engage with it. However, there’s another side to this.

In the hero’s Inner Journey, the Call to Adventure marks the first time they’re asked to come face to face with the flaws of themselves and their world. Until now they’ve lived a life sheltered from the outside, even if only through their own naivety.

#2: Refusing the Call:

The Refusal of the Call is the immediate follow up from the Call to Adventure. Here, most heroes will refuse to believe the flaws they saw through the Call. They’ll be unwilling to answer the Call at this stage.

#3: Meeting the Mentor:

To clear their mind, the hero will need to meet with a mentor figure. This could be another character, a spiritual guide, or even an aspect of the hero’s own mind. Whatever it is, this stage helps push the hero to recognize reality by showing them another example of the conflict, both Inner and Outer, that they’re being called to face.

#4: Finding Allies:

Before the hero can set out on their journey, they need allies to support them. These allies help the hero mentally prepare for the massive change they’re about to experience by giving them a lasting connection to their community and their old self.

#5 Facing the First Threshold:

This much like the traditional First Plot Point of the Three Act Structure. At the First Threshold, the hero begins their Outer Journey, setting off from their community into the unknown world. In their Inner Journey, the hero finally recognizes the Call and sets out hoping to find answers. At this stage, most heroes still believe their lives can return to normal, and it is often this belief that propels them forward—even though they’ll soon find it isn’t true.

Entering the Unknown:

Once the hero has faced the first threshold and stepped outside their ordinary world, they’ve begun the next phase of the hero’s character arc.

This portion of their journey is all about learning.

Here they suddenly come face to face with the truth of what the outside world is—and often, the truth about their own community as well. They’ll likely be beat down a lot at this stage as the story shows them their weaknesses and forces them to grow. They can no longer remain naive if they’re to survive here.

#6: The Road of Trials:

The hero has entered the unknown, and will now have to face the many new challenges and tests of that world. Here they’ll learn a lot about themselves, and will come face to face with the conflict they were warned about in the Call. In their Inner Journey, they’re likely holding on to hopes of returning home, but slowly they will recognize that things were never as simple as they seemed.

#7: Approaching the Cave:

Here the hero will approach a major showdown (The Ordeal), both in their Outer and Inner Journeys. For their Inner Journey in particular, the hero will need to face their old beliefs in new ways and will be tempted to abandon their quest.

In many traditional stories, this manifested as the hero meeting with a goddess or being tempted by an evil female figure—though again, there are no gendered requirements when creating a hero’s character arc. If they overcome this challenge, they’ll have passed a critical test of the hero’s character arc.

#8: The Ordeal:

Here the hero will have to prove all they’ve learned thus far. They’ve overcome their temptation, and now must show that through action. The conflict of the Outer Journey will reach a turning point, and the psychological conflict of the Inner Journey will as well. The hero will need to make a choice here; either embrace their role in healing the wounds of their world, or abandon their quest and their role as the hero.

#9: A Reward:

If the hero succeeded during The Ordeal, they’ll receive a reward. This reward is key both to the conflict of their Outer Journey, and the wounds they’re struggling to heal in their Inner Journey. Their reward could be anything, but it must have both plot and character related aspects. It should reveal the answer they set out to find after the First Threshold.

Returning Home:

The final phase of the hero’s character arc sees them return to their community.

It’s finally time for them to share their newfound knowledge and skills.

The hero has learned the secrets of the outside world, but their community is still suffering. This is when the self-sacrifice of the hero’s character arc really comes into play, as the hero often has to risk losing their newfound life and allies to return home.

They’re no longer the person they once were, but that doesn’t free them from their responsibility to their community. Returning home and healing society is integral to the hero’s character arc, and the final stage in the hero’s development.

#10: The Road Back:

The Road Back is, in many ways, a mirror of the first five stages of the hero’s character arc. The hero will refuse to return home, unwilling to give up their new life (or sometimes unwilling to jeopardize up their old life, depending on the Inner Journey of the hero). This is the hero’s darkest moment, when they’re unsure what all of this has been for and if they’re really capable of fulfilling the hero’s role.

Eventually, if they’re to succeed in the hero’s character arc, they’ll realize they must return. From there, they’ll often receive aid from a spiritual guide or from another powerful source that helps transport them home, often in the nick of time before the conflict of the Outer Journey reaches its head.

#11: Resurrection:

Here the hero crosses the “return threshold,” returning to their community and using all of their skills and knowledge to help heal their world and overcome the conflict of the story. This is the Climax of their story, where all the threads of both the Outer and Inner Journey meet.

#12: Returning With the Elixir:

Finally the hero has returned. They’ve resolved the story’s conflict and put their reward to work, helping their society proper. They’ve overcome the flaws of their world and of themselves, and will help steer their community on a new and better path.

This also comes with the freedom for the hero to live their own life at last, often with a foot in both the outside world and their own community. This resolution is often bittersweet, but triumphant, and it what sets the hero apart from other protagonists.

Ashitaka: The Hero’s Arc of Princess Mononoke

While working on the first draft of this article, I was watching Princess Mononoke by Hayao Miyazaki. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of Miyazaki’s work, and this movie is no exception, but this time I saw the movie in a new light.

You see, the protagonist of Princess Mononoke, Ashitaka, perfectly follows the hero’s character arc.

If you’re not familiar with it, Princess Mononoke follows Ashitaka as he journeys west, searching for a way to lift the curse placed on him when he defeated the demon boar Nago. What he finds outside his isolated village is a world torn by violence.

On one side feudal lords wage war against each another, and on the other the spirits of nature struggle to survive against encroaching humans. As you might imagine, Ashitaka gets caught up between these wars, both sympathetic to the humans but deeply reverent towards the spirits.

Starting in the Ordinary World:

Ashitaka’s time in his ordinary world is short.

He begins the story when the demon boar Nago arrives at his village (The Call to Adventure). At first he avoids it, watching from afar (Refusal of the Call), and an older village guard warns him not to let the demon touch him or risk being cursed himself.

As the demon approaches the village, it traps a group of girls in front of it, and Ashitaka dives in to kill the demon and protect them. In the process he enters the demon’s path and it touches his arm. Though he kills the boar, he is now cursed.

That evening, Ashitaka meets with the elders of his village (Meeting with the Mentor) and they tell him the curse will eat away at him, eventually killing him. The elders talk about how their bloodline is weakening, and how all the human kingdoms outside their isolated village are in decay as well. They mourn Ashitaka’s loss, but know he cannot stay.

However, before he goes they tell him to journey west in hopes of lifting his curse. Ashitaka leaves under the cover of night, bringing his loyal elk, Yakul, with him (Finding Allies). He and Yakul disappear into the darkness of the forest (Facing the First Threshold).

Entering the Unknown:

Having officially left home, Ashitaka makes the long journey west, facing a variety of challenges along the way. He gets caught up in a battle with samurai and discovers his cursed arm gives him increased strength, and a traveling monk tells him to seek the mountain of the Deer God to find answers.

Later, he helps rescue two men who were thrown from a cliff, and they warn him about the war between the people of the Ironworks and the nature gods that live in the Deer God’s mountains. Ashitaka even sees the Deer God while traveling through their woods, and discovers that his cursed arm moves on its own, still imbued with the raging spirit of the demon boar (Road of Trials).

The plot of the story moves more quickly when Ashitaka finally reaches the Ironworks. There he discovers the humans have been clearing the forests and killing the local gods to mine more iron. When he finds out their leader, Lady Eboshi, personally killed Nago and turned him into a demon, he feels enraged by her cruelty.

However, Lady Eboshi shows him another side of the Ironworks; not only is it a shelter for the sick, but it provides safe haven for people who otherwise would face terrible abuse from those more powerful than them. Still, Lady Eboshi is bent on killing the Deer God once and for all. Ashitaka isn’t sure what to think (Approaching the Cave).

At first, Ashitaka helps around the Ironworks, unsure if he should stay or go. When he is about to leave, however, the wolf-princess Mononoke arrives intent on killing Lady Eboshi. Ashitaka knows Eboshi will kill her if he doesn’t stop them and fights to protect Mononoke, getting shot in the process.

He carries Mononoke out of the Ironworks and back to the wolf gods who raised her, before passing out from his wound (The Ordeal). At first Mononoke wants to kill him, but realizes he is on nature’s side. She and the wolves take him to the Deer God’s forest, where the Deer God heals him. However, the curse remains; it seems the Deer God won’t save him after all (A Reward).

Returning Home:

Ashitaka struggles with the fact that he is still cursed and is unsure what he should do next. Meanwhile, the war between the humans of the Ironworks, the opposing samurai, and the nature gods escalates into a massive battle. Ashitaka goes to the wolf gods and tries to explain that humans and nature can coexist, but they refuse to believe him. Eventually Ashitaka gives up, leaving the Deer God’s forest and Mononoke behind.

However, Ashitaka won’t surrender so easily. When he passes the Ironworks and sees that it’s under attack, he steps in to protect it—Ashitaka races to find Lady Eboshi so she can send reinforcements to protect the people at the Ironworks.

In the process he realizes Mononoke has gone to war with the humans, and that one of the other leaders of the nature spirits is horribly wounded. They’re heading for the Deer God’s forest, and Ashitaka must stop Lady Eboshi from following them (The Road Back).

Upon reaching the forest, Ashitaka saves Mononoke from certain death, but cannot stop Lady Eboshi, who kills the Deer God and steals his head. As soon as he loses his head the Deer God becomes a massive demon, consuming and killing everything it touches.

Ashitaka and Mononoke race to retrieve the head and warn the Ironworks of the coming calamity. Eventually, they force Eboshi’s allies to relinquish the head and return it to the Deer God, seeming to die in the process (Resurrection). However, when the Deer God regains his head, a divine wind blows across the mountains.

Not only are the forests healed, but the sick people of the Ironworks are as well. Ashitaka and Mononoke are both alive and Ashitaka’s cursed arm is healed. While Mononoke is unwilling to come live at the Ironworks with him, she promises to live in peace alongside the humans. Ashitaka returns to the Ironworks, forging a new balance between nature and humanity (Returning With the Elixir).

Writing a Hero’s Character Arc for Your Story

If you’re wondering how to write a hero of your own, Ashitaka’s journey is a great example of the hero’s character arc in action.

Not only does he follow every beat of the hero’s character arc, but he shows how the Outer and Inner Journeys of the hero interact and weave together into a powerful story. When you sit down to write a hero of your own, start by considering what flaw, sickness, or weakness their society has. What does their society need to grow and prosper? Most importantly, what does their society need to learn to become better?

With that information you can build the basic framework of your hero.

The world around Ashitaka was decaying because humans and nature were at war, so his Hero’s Journey ties into a quest to unite the two. While Ashitaka was a flat arc character, your hero can follow any of the three primary character arcs—positive, negative, or flat—as long as the ending wraps around to them solving the problems of their community.

This defines them as a classic hero, though it’s possible for them to be a failed hero (negative arc) that not only fails to grow into a better character, but fails to lift up their society.

Of course, there are plenty of other archetypes beyond the hero archetype, and Campbell and Vogler discuss many of them. If you want to learn more about the Hero’s Journey and the characters you can find within it, check out these articles next:

—–

As you can see, the hero’s character arc follows many of the common patterns seen in the three primary character arcs all characters—regardless of hero status—follow. However, what sets it apart is its focus on the hero’s return to their community.

To truly be a hero, it seems we have to not only grow into a better person, but into a leader as well. 🙂

The best description yet! Or is it because it confirms that without knowing this my character arc is right on track!

Thank you Marta. 🙂 I’m glad to hear you were already ahead of the curve. I’ve found that many writers pick up on these character arcs subconsciously over the years, and many are shocked it’s actually an official structure when they find out!