How to Write Believable Children in Fiction

Creating realistic characters isn’t always easy.

From understanding their unique personality to unpacking their backstory and goals, it takes a lot of careful planning to craft a character from scratch. Combine that with a wildly different perspective on the world, and it’s no surprise that things get even harder—which is why writing child characters is such a tricky process.

Fortunately, writing believable children is much like writing any other character. The key is to let go any assumptions you might have, and instead consider the world through their eyes. So, let me walk you through five ways to write with your inner child!

The Problem with Adults Writing Children

Contents

Writing a diverse cast of characters from different backgrounds, genders, races, and more is a tricky task. After all, most of us rely on our own beliefs and history to help us write our characters. If we don’t have any shared experiences to draw from, it’s easy to fall back on stereotypes to fill in those gaps.

Writing a diverse cast of characters from different backgrounds, genders, races, and more is a tricky task. After all, most of us rely on our own beliefs and history to help us write our characters. If we don’t have any shared experiences to draw from, it’s easy to fall back on stereotypes to fill in those gaps.

However, there is one group we’ve all been a part of—and that is children.

So, why do adults fail to write realistic child characters in their novels? Well, while we’ve all been children before, it’s easy to forget what being a child is like. Depending on how old you are, decades might have passed since you were last a kid, meaning you’ve had plenty of time to buy into the stereotypes often associated with children.

You might believe that:

- Children are unreasonable and irrational

- Children are incapable of understanding the world

- Children can’t care for themselves, no matter their age

- Children are all cute and innocent, without exception

- Children are a monolith

All of these (frankly untrue) beliefs can color the way you write child characters in your stories—when in reality, writing children isn’t much different than writing any other character!

So, how should you approach this?

Well, the trick is to think of the world from their perspective, while recognizing the unique experiences and quirks children often have…

5 Tips for Writing Realistic Child Characters

Consider Their Point of View:

First up, perhaps the best way to write realistic children is to consider their perspective.

When you were a child, your experiences were likely very narrow. Your life was defined by your immediate surroundings, meaning every event was a much bigger deal. On the other hand, compare that to now. You’ve had the opportunity to meet new people, face challenges, and figure out what you can truly handle. This gives you context for your experiences, and thus changes how you handle the events in your life.

For example, a four-year-old is likely to react more strongly to being fussed at by their parents than an older child. At such a young age, making their guardian angry is an emotional event. However, by the time you’re twelve, you can better gauge your parents’ reactions. You’ve likely been fussed at plenty of times for things both small and large. You know you don’t need to panic, because you’ve been through this before.

The same goes for how your child characters understand their world.

As a young child, you’ll likely assume your view of the world is the only option—you simply don’t have other experiences to compare it against. After all, if the only dog you’ve ever met was brown, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume every dog is brown! This is how you end up with kids insisting that you couldn’t possibly have a yellow dog. They’ve yet to realize that their experiences aren’t the only option out there.

So, when writing child characters, make sure you consider their perspective. What experiences have they had, and what do they still need to learn? These things will play a massive role in determining how they behave in different situations.

Watch Their Emotional Jar:

Next, one of the biggest sins adults commit when writing children is trivializing their feelings.

You see, all of us have a limited capacity for handling our emotions. This is our emotional jar, and when it overflows, we can’t help but express what we’re feeling. This is why you might burst into tears over something you know is insignificant, like the mail being late. Your emotional jar was already dangerously full thanks to other stressors in your life.

What’s more, this jar also grows with age. This means your child characters will seem to react more strongly to the events in their life, because their jar overflows much more quickly. They’ll need to find an outlet for their feelings more often, and they’re more likely to get upset by seemingly small things.

The real difference between adults and children is how they handle that jar.

As we mature, we—hopefully—learn how to process our emotions in productive, safe ways. This is why a toddler screams when they’re upset or a child slams their bedroom door. Their emotions are entirely valid, but the way they handle them is determined by their maturity.

Of course, this isn’t always a linear progression. Plenty of adults have small emotional jars, and some kids might have unusually large jars. Likewise, not all adults know how to handle their feelings, while some kids are surprisingly mature.

Still, the older you are, the larger your jar will likely be. Rather than openly sob when they’re sad, your older characters might just become quiet and glum, while children who used to scream in excitement will instead grin and laugh as they age. Either way, their emotions have a source—and your job as a writer is to understand and respect that source.

Develop Their Character:

With that said, a lot of how we behave is determined by our nature—and that’s true whether your character is a child or an adult.

Just like adults, children have their own personality and preferences, and these will influence how they express themselves. Some kids are subdued and shy, while others are loud and boisterous. Some child characters will constantly demand to be the center of attention, while other children would rather disappear than get stuck in the spotlight.

This is why it’s so important to treat child characters like any other character.

Just like you plan out your adult characters’ personalities and history, you should do the same for your child characters:

- What are their likes or dislikes?

- What are they afraid of?

- What do they desire most?

- What goals are they working towards?

While you might think your child characters won’t have any motivations of their own, you’d be surprised! The best child characters follow the same character developments rules as any other member of your cast, meaning they need some kind of goal to pursue. Even if that goal is simple—like saving enough money to buy a new bike—it should be present, along with every other element of a well-developed character.

Pay Attention to Their Environment:

Now, I mentioned history a moment ago, and that’s something I want to circle back around to.

You see, it’s easy to assume that backstory isn’t important when writing children, because they haven’t been alive long enough to experience many major events. However, even if your child character has led a mundane life, that doesn’t mean their past experiences don’t matter.

Our childhoods are our most formative years. The way we’re treated by our family shapes how we view the world, and any major events we do experience will leave a massive impact on our minds. Even seemingly insignificant things like doing chores or spending summers away from home can have unexpected effects on our growth.

This is why, when writing child characters, you shouldn’t overlook their history.

Something as simple as the environment they grew up in or the values their family passed on to them will play a big role in who they become as a person—as well as how they behave as a character.

Treat Them Like an Equal:

Finally, my last tip is this: don’t look down on the kids in your story.

Just like adults, children have problems, fears, and desires that feel important and pressing to them, even if they seem trivial to us. This means that, if you want to write child characters that aren’t just caricatures, you need to respect their viewpoint.

Don’t assume kids are stupid or incapable of understanding their world. Likewise, don’t assume all children are fountains of sage-like wisdom. Instead, take the time to get to know your child characters as complex people, just like every other character you might write.

This is doubly true when writing teenagers.

While this article is mostly focused on preteen kids and younger, far too many adults treat teens like some kind of illogical anomaly. Yet, teens follow the same rules as any other character! They’ll have their own personality, goals, and views, and they’ll also have perfectly valid emotions filling their emotional jars.

So, if you’re writing any teenage characters, make sure you write them with the same level of respect and care you would show any other character.

How I Use “Jar Diagrams” to Write Children

With that said, let me show you how I put these tips to work in my own writing practice.

You see, I’m currently working on a sword and sorcery fantasy novel called The Child Hunters—and, as you can probably tell from the name, the kids in this story play a fairly large role! This means I’ve been creating a lot of child characters, and in the process I’ve developed a tool I like to call “jar diagrams.”

Essentially, these diagrams are a simple visual I use to help me understand how reactive the children I’m writing are when compared to my other characters. Combine that with my usual character sheets—which list things like their appearance, backstory, and personality—and I end up with a pretty good understanding of how that child might behave.

So, what do these jar diagrams look like?

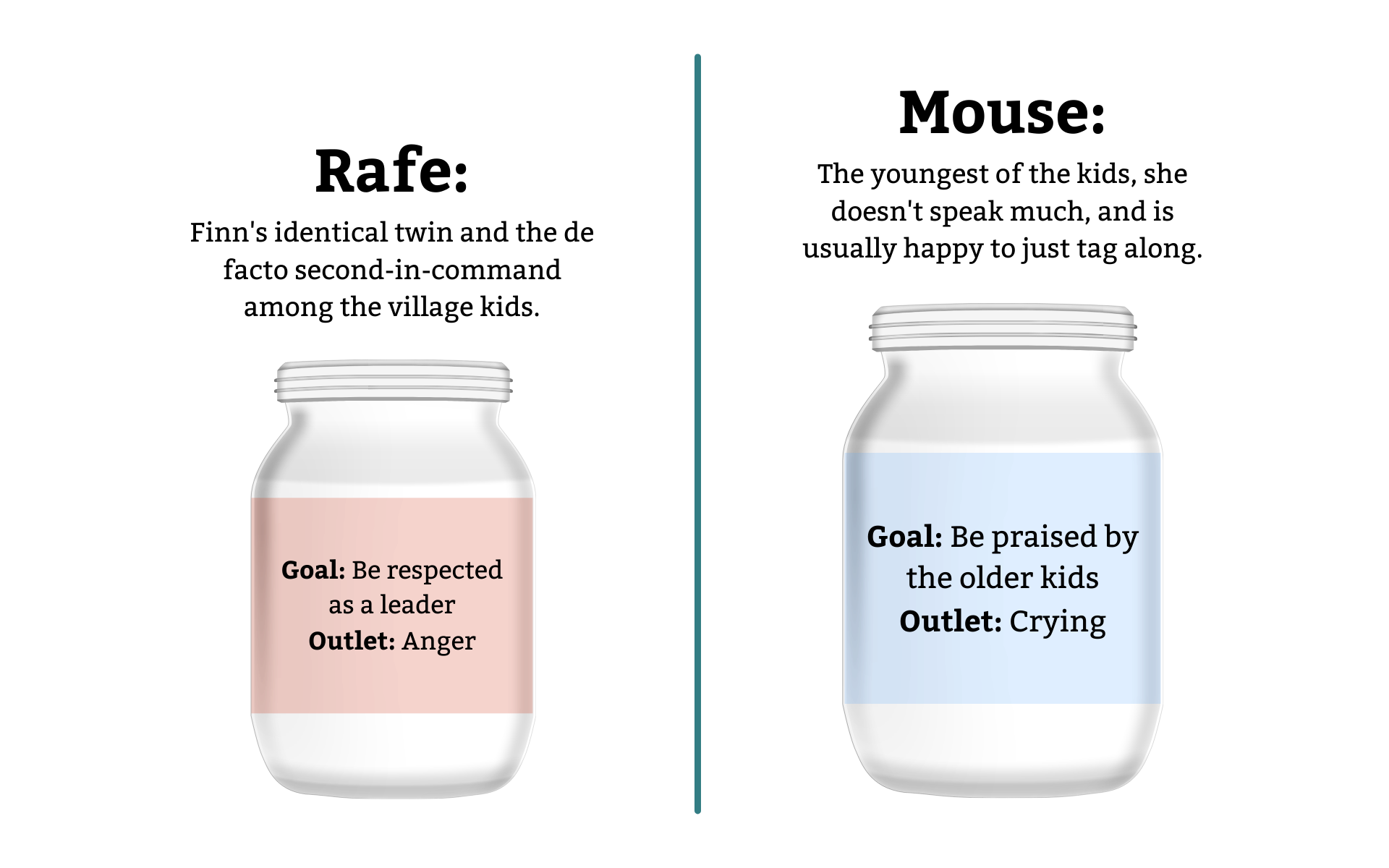

Well, the easiest way to explain them is to show you! As an example, one of my child characters named Rafe has a relatively small jar, and that jar is labeled “anger.” This is his primary emotional outlet, meaning when he gets overwhelmed, he’ll likely respond by yelling at the nearest person—and, since his jar is smaller, it also means he gets angry fairly easily.

In contrast, Mouse is a younger child character, but she also has a larger emotional jar than Rafe. This means she isn’t prone to strong reactions, but when her emotional jar does overflow, she tends to express those emotions by crying.

You’ll also notice that these jars include each child’s primary goal. Rafe wants to be seen as a leader, and so he hates being shown up by others. Meanwhile, Mouse is just happy to be included in the group, and wants nothing more than to earn the older kids’ praise.

Of course, you don’t need to draw literal jars for this to work.

Even just jotting down a few extra notes about how your child characters handle their emotions can go a long way towards helping you write them. Still, I like these little diagrams. They’re extremely simple, but they’re also fun to draw and encourage me to think more carefully about how my characters express themselves.

Best of all, this goes for adults too. Not all adults have the same sized jars, and no matter how big their jar is, it’ll still overflow on occasion. So, if you find this process helpful for your child characters, it might be worth drawing these diagrams for the adults in your cast too!

The Importance of Perspective

At the end of the day, the most important thing to understand as a writer is perspective.

Your characters’ perspectives will tell you how they view the world, how they think about themselves, and how they’ll process the events of your story. Plus, it’ll also give you a window into their behavior. After all, something that seems minor to you might be a major, life-changing event to someone else.

When writing child characters, this is extra important.

It’s easy to forget what life was like when we were children, but with a bit of time and patience, you’ll hopefully find that children make a lot more sense than we often give them credit for. Ultimately, just remember to respect their feelings and take their views seriously—even if they seem silly a first to us grownups! 🙂

Thank you so much for the article! I’ve been trying to develop two child characters using methods designed for adult characters, and it’s been driving me a bit crazy. Your insights are truly helpful. I agree with the comment above, too, about the emotional jars different characters have. In psychology I’ve always heard it referred to as a container, and it’s a fascinating subject. I’ll be sure and bookmark your site to use a reference. Thanks again!

One of the main characters of my story is a 10 year old boy so this was very helpful. The entire emotional heart of the book hinges on the child character and adult character’s relationship and its pivotal that the child is a well developed character. This is has been such good advice, especially about the emotional jars, never thought about what happens when they overflow, even for my adult characters.