The Ultimate Guide to Motivating Your Protagonist

Massive storms, alien invasions, and killer pigeons all have one thing in common…

These potentially deadly events have all been used as protagonist motivation. In fact, raising the stakes through extreme measures is a staple of many genres, and is a common way for writers to motivate an otherwise unenthusiastic protagonist.

Someone’s going to die, get captured, get hurt, et cetera… The protagonist is the hero, so of course they won’t let that happen. It all makes so much sense! But does it really?

While these dramatic methods can work, they don’t work in every situation. More importantly, they leave your story missing out on the more nuanced and multi-layered ways you could be motivating your protagonist. Ask yourself—what will be more meaningful to your reader? A protagonist motivated by outside circumstances, or one driven by their own, innate needs?

Why Every Protagonist Needs Motivation

Contents

Regardless of what their motivation is, every protagonist needs one. That’s why you see so many stories creating outlandish conflicts in an attempt to get their lead character involved. It wouldn’t be a story without some motivation moving it forward.

Your protagonist’s motivation should serve two key roles within your story:

Plot: Their motivation should force them to engage with your story’s conflict and, as a result, move the action forward.

Character Arc: Their motivation should reveal who they are as a person, allowing your audience to identify with them as they work through their character arc.

Without a strong motivation, your protagonist can quickly become meaningless to your story’s plot. Worst-case scenario, they’re so lacking in motivation that your plot never moves forward at all, you never hit the important story milestones you need, and your conflict languishes.

Of course, there are differences between “motivation” and a “good motivation.”

Preventing the end of the world has the potential to be a good motivation, but only if it falls within a few criteria:

- Their motivation should reveal something about them as a character.

- It should feel credible when compared to other elements of their character, like their personality, goals, backstory, or beliefs.

- Their motivation should create tension in your story when it’s challenged by the broader conflict of your novel’s plot.

The importance of motivations goes beyond your plot or character arcs as well. Your protagonist’s motivation (or any character’s motivation for that matter) is what makes your reader stick around to see your story to its end. After all, how many of us have enjoyed watching flawed protagonists, just because their motivations were so interesting?

The Two Types of Character Motivation

Of course, your protagonist won’t go through your entire story with just one motivation—that would be too easy. 😉

Instead, your protagonist will have a variety of motivations that can be divided into two distinct types: story motivations and scene motivations.

Story Goals: These are motivations that drive your protagonist throughout your plot, from beginning to end. They’ll likely only have one or two throughout your novel.

Scene Goals: These are the smaller, scene-by-scene goals of your protagonist as they react to specific events in your story.

If you realized that these are closely related to the two types of conflict in your novel, then you’ve been doing your homework! Your protagonist’s story goal pushes them to engage with your novel’s macro conflict, while their scene goals are how they react to your micro conflicts.

Here’s an example from Mulan (1998):

Story Goal: Mulan is motivated to prove her worth to her family. As a result, she joins the Chinese army and is pulled into the conflict between China and the Huns.

Scene Goal: Mulan experiences various scene motivations ranging from “gain the acceptance of the other soldiers,” “don’t get caught as a woman,” and “save Shang from falling to his death.” Each one corresponds to a specific event in the plot.

Motivating Your Protagonist Based on Human Psychology

Since your protagonist’s motivation is such a driving force behind your story’s conflict, I hope you’re starting to see why overly simple “end of the world” motivations don’t always cut it. When an external motivation is forced on a protagonist, it won’t always line up with the best practices we’ve discussed above.

Instead, using nuanced motivations that are tied to your protagonist’s character will often be the way to go (and can still include some nice world ending goodness, if that’s what you enjoy). Of course, using those nuanced methods requires a strong understanding of what motivates characters to begin with.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

To start, I want to say thank you to Kristen Kieffer for bringing this up in her awesome post on character motivations. I had been spending a few hours drafting this post and trying to figure out how to explain the psychological side of character motivations, but it turns out Abraham Maslow beat me to it all the way back in 1943!

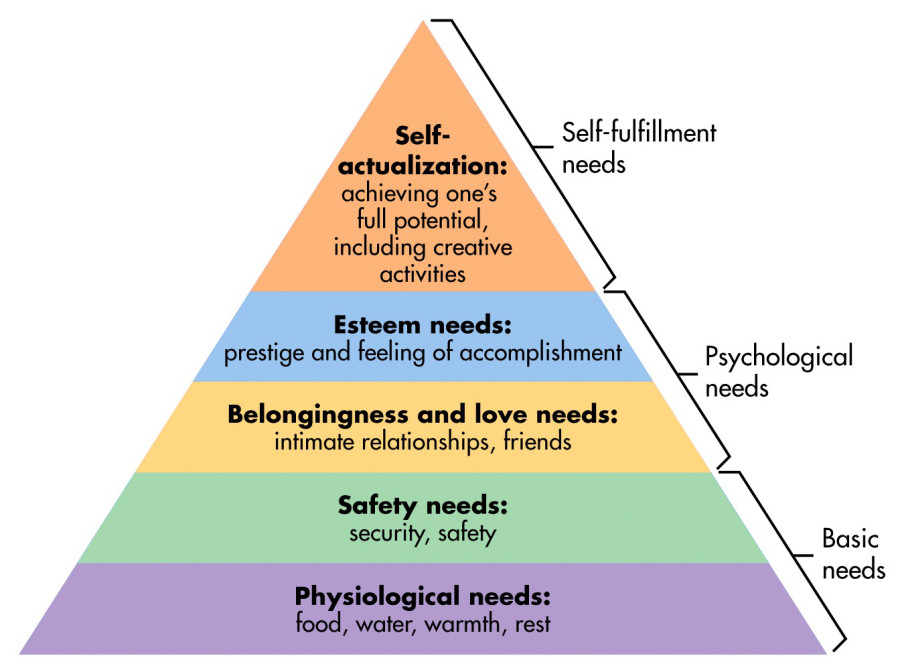

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a psychological theory that divides human motivations into five categories:

- Physical Needs (like food or water)

- Safety Needs (like safety from violence)

- Love Needs (like family and friends)

- Esteem Needs (like praise and accomplishment)

- Self-Actualization Needs (like a life’s purpose)

In Maslow’s theory, our most basic needs exist at the bottom of the hierarchy while higher motivations are at the top. In his view, we can’t address complex issues like our life’s purpose until we’ve secured our safety and physical well-being first.

Of course, since he published this idea there’s been a lot of debate on its validity, and I won’t attempt to prove or disprove it here. Whether or not this hierarchy is as strictly separated as he said isn’t important for your novel. What is important is that Maslow’s Hierarchy provides an easy way to think about your character’s motivations and how they relate to their fundamental needs.

For a motivation to be meaningful to your protagonist, and therefore impactful to your reader, it needs to touch on one of these needs. Some of the best story goals deal with higher needs like love or esteem, while basic needs work great for scene goals (though this isn’t a strict rule)

Even better, a truly compelling motivation will layer multiple needs together.

The Benefit of Layering Motivations:

Layered motivations are both more complex and more satisfying for your reader.

For example, instead of your protagonist being motivated by physical hunger alone, maybe they’re also pushed forward by a desire to be accepted by other people. Thus, when they’re finally able to share a meal with a group of potential allies, you’ll have addressed both their physical and esteem needs.

There’s no doubt that avoiding starvation is a powerful motivator, but by layering a higher motivation alongside it, you create a more nuanced and multi-dimensional goal.

This can go even deeper into your character’s core identity.

In the classic western Shane (1953), the lead character Shane is motivated by two conflicting story goals: A desire to protect the homesteaders (safety and love needs) but also a desire to lead a peaceful life (self-actualization needs).

These conflicting story goals make Shane a more sympathetic character, one the audience mourns for as he struggles to reconcile both of his desires. Just like Shane, your protagonist’s motivations don’t need to be linear, and can exist alongside one another to great effect.

Finding the Right Motivation for Your Protagonist

It’s easy to get caught with a protagonist who lacks the motivation to take action. If you’re struggling to motivate them through superficial (usually world-ending) stakes, they can end up doing nothing but react to outside events. This might not seem bad on the surface. After all, half of Act 2 in the traditional Three Act Structure is dedicated to your protagonist reacting to the conflict.

The problem arises when your protagonist never becomes invested in your plot for their own sake, and thus never takes an active role in your story. Instead, they’re just being pulled along for the ride.

At that point, you have to wonder if they deserve to be your protagonist at all. To fix this, you need to dig deeper into that protagonist’s character, identity, and desires to find what truly motivates them.

Finding Your Protagonist’s Story Goal:

You’ll want to start with their story goals. These are the one or two motivations that’ll get them involved in your plot and push them to take action. They may stick with a single goal from beginning to end, or they may have to abandon their old goal for a new one as they go through their character arc.

Here are some examples you might be familiar with:

Star Wars: A New Hope: Luke is motivated by a desire to weaken the Empire. Luke has one desire from beginning to end.

Casablanca: Rick is motivated by two conflicting desires: to protect his own interests and to support the French Resistance. Rick struggles between two motivations until the Climax.

How to Train Your Dragon: Hiccup is motivated by a desire to be accepted as a Viking and later to be accepted for who he really is. Hiccup gives up his old motivation for a new one as he grows.

To find your protagonist’s story goal, start by asking a few questions:

- What goals do they have?

- What do they fear? What might they be motivated to do to avoid this fear?

- How do they think of themselves? Do they want to maintain or change this identity?

- What lesson will they learn? How can you force them to learn this through their motivations?

- What is their central problem? Their motivation will often be their attempt to solve their central problem.

- Are they seeking answers, and if so, what for?

- What do they feel they’re responsible for? What do they want to change about their world?

- What cause are they fighting for, or do they have a dream they want to achieve?

Brainstorming Possible Scene Goals:

While your protagonist’s scene goals are certainly related to their story goal (since that influences all of their behavior), their scene goal are more dependent on plot. These form as a reaction to your plot and push your protagonist through specific scenes and events.

Here are (just a few) examples from the movies we discussed above:

Star Wars: A New Hope: At different times, Luke is motivated to find R2-D2, escape the trash compactor alive, and later escape the Death Star with Leia and Han.

Casablanca: Rick is motivated to avoid Ilsa, then to get answers from Ilsa, and later to protect her and Victor from the Nazis.

How to Train Your Dragon: Hiccup is motivated first to kill a Night Fury, then to learn more about it, then to help Toothless fly.

To come up with your protagonist’s scene goals, look to your plot:

- What are the immediate challenges they’re facing?

- What are they trying to avoid in that scene?

- What is hurting them and how do they want to fix it?

- What is their story motivation and how can they work towards achieving it?

Why Your Villain Needs a Compelling Motivation Too

For most of this article we’ve just been discussing your protagonist. While I’m sure you’ve realized that many of these principles apply to your other major characters as well, where does your antagonist fit into all of this?

Antagonists are portrayed as “just evil” far too often in both books and films. Give them a creepy mustache to twirl, a maniacal laugh to frighten us with, and a few bad deeds under their belt and you figure they’re good to go. Not so.

“He’s the bad guy just because… well, he’s bad. Isn’t that enough? Definitely not enough.

Next to your protagonist, your antagonist is the single most important character in your story. Skimp on him, and the entire story—including the protagonist—will suffer as a result.” – K.M. Weiland, How to Properly Motivate Your Bad Guy

Your antagonist needs strong motivations for the same reason your protagonist does.

It makes them feel credible to your reader, reveals something about them as a character, and actively pushes them to stoke the conflict of your plot. What makes a good villain scary isn’t their facial hair or evil eyes, but the resolve with which they pursue their goals.

Why Your Protagonist Isn’t a Suitable Motivation:

Equally important as having a strong motivation is what that motivation is.

Just like too many villains are cardboard cut-outs without the motivation to back them up, too many villains’ motivations center only on stopping the protagonist. The question then becomes… Why? What about your protagonist is so special that they’re the only goal your antagonist could come up with?

The answer to that question is rarely compelling. Even in famous stories where the protagonist is truly “special,” the villain’s goals are external to the protagonist. The protagonist just so happens to get in their way:

Harry Potter: Voldemort is motivated by a desire to become immortal and create a “pure-blooded” world in his vision.

The Lord of the Rings: Sauron is motivated by a desire to reunite with the One Ring in order to regain his full power and conquer Middle Earth in the name of his god.

Star Wars: Darth Vader is motivated by a desire to destroy the rebel cause in order to advance the power of the Dark Side and please his master.

You’ll notice that none of these villains are motivated to destroy (enter protagonist’s name here). Fighting the protagonist is simply a means to achieve their story goal because the protagonist keeps getting in their way.

Speaking of Darth Vader, he acts as a great example of how valuable complex motivations are for antagonists.

Not only was his original story goal in A New Hope credible and frightening, but that goal evolved by the third movie. It came into conflict with another goal—to protect his son. This is how Darth Vader was redeemed. Slowly but surely, his conflicting motivations battled it out until one shone through.

The Value of Motivation

Whew… Since motivations are such a core part of your story, there was a lot to cover, but I’m glad you stuck with me until the end! 🙂

When you think about your protagonist’s (and antagonist’s) motivations, you should start to see their role in your plot coming clear. They’re no longer an unenthusiastic character being dragged through the conflict by coincidence—now they’re an active player, shaping and being shaped by your story.

Just as it should be!

I love the questions you offer to help me figure out my protagonist’s motivations. Thanks Lewis.

I’m glad you found them helpful Rachel! 🙂